from Henley-on-Thames to the Somme

The start of the Battle of the Somme is the most significant First World War anniversary that falls during Henley Royal Regatta. In 2016, Henley coincided with the Somme’s centenary commemorations.

Cities, towns and villages mourned the huge losses from this first major action for the thousands who had volunteered for the Army during 1914 and 1915 many of whom joined-up alongside their friends in what became known as Pals Battalions.

Although there wasn’t a Pals Brigade for oarsmen, Henley Races, published in 1919, includes a chapter entitled Last Post which lists 273 Henley competitors (including 14 coxes) who fell during the war. It provides an insight into the impact of the Great War on Henley and the place of rowing in Edwardian society.

Educated at Radley and Wadham College Oxford, the book’s author was Sir Theodore A. Cook. He was editor of The Field and a timekeeper at Henley. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography records that Cook “turned The Field in a propagandist direction” during the First World War. He was also a campaigner for “the preservation of true sportsmanship” and the amateur ethos.

Cook’s list reflects the definitions of “amateur” used by Henley and the Amateur Rowing Association at that time. “Manual labour” and “menial duty” exclusions effectively restricted the right to compete at Henley and other leading regattas to the universities, public schools and those clubs serving the upper echelons of the middle classes.

Cook doesn’t explain how the list was compiled, but records from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge would appear to have been an important source, as he comments that “Cambridge has made a more complete record of her soldiers than Oxford.”

264 of those listed served in the Army, five in the Navy and 11 are either indicated as having been attached to the Royal Flying Corps or, from 1 April 1918, as serving in the newly constituted Royal Air Force.

Colleges are identified for 180 – two thirds – of the 273. The largest contribution to the list – 26 – came from Trinity College Cambridge: 16 from First Trinity Boat Club and ten from the Third. Magdalen was the most prominent Oxford college, contributing 14. E.D. Powell of Trinity College Dublin was the only oarsman identified as having come from a non-Oxbridge UK institution although G.D. East, killed while serving as a Captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, is linked to both St Bart’s Hospital and Thames R.C..

42 individuals had competed in the Boat Race – 21 from each university. Collectively they had amassed 71 Blues of which 40 were awarded by Oxford. 27 had been members of 40 winning Boat Race crews.

Twelve had competed at either the 1908 or 1912 Olympic Games. G.B Taylor killed serving as a Lieutenant in the Canadian Highlanders and formerly of Trinity Oxford and Argonauts R.C., had competed at both. Four were Olympic Champions.

There is very much less information about club affiliations. Only thirteen English clubs are named compared with 36 Oxbridge colleges. Total club losses of 67 are headed by London R.C. (15) and Thames (14).

While not all oarsmen get to race at Henley, the limited coverage of clubs suggests that Cook’s list understates the overall loss of Henley competitors, let alone oarsmen. Hear the Boat Sing recounts the stories behind several club war memorials†. Several oarsmen commemorated by their clubs are mentioned in the detailed records of the regattas from 1903 to 1914 that make up the bulk of the Henley Races book but are missing from the Last Post chapter.

One example is A.J. Shaw. He is commemorated on the joint memorial erected on Trent Bridge by four Nottingham clubs and raced in the Wyfold for Nottingham Union R.C. in 1914 but doesn’t appear in Cook’s list.

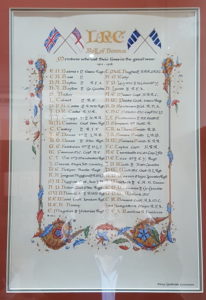

In a similar vein, Chris Dodd’s history of London R.C., Water Boiling Aft, records that 90 members of the club volunteered between the outbreak of war and the end of 1914 and that 50 members did not return. The 50 names are included in a calligraphic roll-of-honour. Of these, only 12 appear in Cook’s list. Conversely, three oarsmen identified as London members by Cook do not feature in the club’s commemoration.

Seven schools are identified against 91 of the names: Bedford (15), Cheltenham (1), Eton (41), Radley (19), Shrewsbury (10,) Winchester (1) and Beaumont College (4)‡.

Cook corroborates Chris Dodd’s observation that oarsmen had been quick to join the flood of volunteers after the outbreak of war: “After July 1914, however, all rowing stopped except at schools. Nearly every boat club known at Henley — I am glad to record it — had sent its able-bodied men to the Army or the Navy before a whisper of conscription had been heard.” He continued, “Both the University crews, and all the British competitors in final heats at the Henley of 1914, were in naval or military training by the Christmas of that year.”

Cross-referencing the Last Post list against the records for the 1914 Regatta reveals that the Christ’s Cambridge Ladies Plate eight and Jesus College Thames Cup crew lost four members each while the London R.C. Grand, Eton and Radley Ladies Plate crews and Selwyn College Thames Cup crews all lost three. The Brasenose four that raced in both the Wyfold and Vistors lost three members while the 3rd Trinity Goblets pair of E.G. Williams and Le Blanc-Smith were both killed.

In The English, A Social History, 1066-1945, Christopher Hibbert states that 750,000 volunteers had enlisted by the end of September 1914 rising to more than a million by the end of that year.

Last Post suggests a high correlation between amateur oarsmen and the officer class. Just ten of the 273 were privates or non-commissioned officers.

Hibbert notes “A high proportion of the killed and wounded [in the First World War] were officers, many of whom had received their commissions on the strength of certificates granted by the Officer Training Corps of the public schools and universities, and many more of whom had gone straight from school to France as second lieutenants before reaching that not very high standard of efficiency that the getting of a certificate demanded.” About one in five officers from public schools were killed: the exact numbers for Eton were 1157 fatalities among the 4852 Old Etonians who served overseas.

53 of the 273 – a fifth – held the rank of 2nd Lieutenant while 88 – a third – were Lieutenants. 82 were Captains while 20 had achieved the rank of Major. The list also includes six Lieutenant Colonels and two Colonels. (There were also four Reverends and one cadet.)

26 of those named had been awarded the Military Cross (one with a Bar), four the Distinguished Service Order, one the Distinguished Service Cross and one the Croix de Guerre. Medals won on the water at Henley included 27 in the Grand, 32 in the Ladies, 12 in the Thames, 5 in the Stewards, 19 in the Wyfold, 18 in the Visitors, two in the Goblets and four in the Diamonds.

The Somme Campaign

Stretching along 14 miles of the Western Front between Maricourt in the south and Serre in the north, the Somme was one part of an Allied master-plan hatched in December 1915 to defeat Germany with simultaneous large scale attacks on the Western, Russian and Italian fronts during the summer of 1916.

Giuseppe Sinigagli, a member of Lario Club Como, was one of the representatives of overseas clubs mentioned in the list. The 1914 Diamonds winner died on 10 August 1916 serving as a Lieutenant on the Karts Plateau on the Italian front.

The first day of the Somme offensive resulted in 57,470 British and Commonwealth casualties of whom 19,240 were killed. July 1st 1916 holds the record for the highest number of casualties suffered by the British Army in a single day. By the end of the 141-day campaign on 18 November, more than a million men on both sides had been either killed or wounded.

Although Cook’s list doesn’t record where the fallen fell, it has been possible to confirm that at least four of the 273 died on the first day of the Somme.

Two of these four were 2nd Lieutenants.

Charles Treverbyn Gill, attached to the 22nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment, was a graduate of Exeter College Oxford and a member of London R.C.. As a junior officer in an infantry regiment, Gill would almost certainly have led his unit “over the top” when the advance started at 7.30 am on what was a bright summer morning. As such, there is a high probability he would have been one of the early casualties. He’s commemorated at the Peronnne Road Cemetery, Maricourt.

In 1915, Christopher Monckton, had raced for Eton II against Beaumont School in one of the private matches that were virtually the only rowing on the Henley reach after the outbreak of war. From two Eton eights that raced that summer, no fewer than six fell in the War. A year later, Monckton was a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Irish Fusiliers but attached to No 13 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corp. He was killed in action while flying BE2c 2648 having taken off from Savy aerodrome on a bombing mission at 14:40. His plane was last observed in combat with a German aircraft. The 18-year old was laid to rest in Mons-en-Chaussee cemetery.

The other two Henley oarsmen identifiable as having been killed on 1 July were both part of a fatally-flawed and ill-fated “diversionary” attack on Gommecourt. From this heavily fortified German salient the main British advance towards Serre at the northern end of the Somme front could be threatened by flanking fire.

Bernard Sydney Harvey and John Robert Somers-Smith were both Captains in the London Rifle Brigade which was part of the 56th (1st London) Division deployed with the 46th (North Midland) Division against Gommecourt.

“Gommecourt was particularly easy of defence, and from the shape of the ground it was a most difficult place from which to disengage troops in the event of partial failure or incomplete success.”

Official History of the War, Military Operations: France & Belgium 1916, Vol 1.

Born in August 1888, Harvey had raced at Henley for Trinity College Oxford in the Wyfold and Visitors in 1908 and in both the Ladies Plate and Thames Cup in 1909. (Doubling-up was commonplace at Edwardian Henley.) He had also trialed for the Oxford Blue Boat in 1909.

Somers-Smith won the Ladies Plate with Eton in 1905 and competed again as Captain of Boats in 1906. He stroked and steered Magdalen College Oxford to victory in both the Wyfold and Visitors in 1907 and then the Stewards and Visitors in 1908.

As well as trialling for the Oxford Blue Boat in both 1907 and 1908, he reached the semi-final of the Grand in 1908, losing to Gent. He went on to win gold at the Olympic Regatta of the 1908 London Games – also held at Henley – where he stroked his Magdalen coxless four to victories over Canada in a heat and Leander in the final.

He had been awarded the Military Cross for gallantry at the 2nd Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915). His elder brother Richard, a double rowing blue for Oxford, had been killed at Hooge in the Ypres Salient on 30 June 1915 – a year and a day before the start of the Somme offensive.

The two captains were among 2,026 who paid the ultimate price at Gommecourt. Like so many thousands of those who fell on the Western Front, they have no known graves. By coincidence, their names are adjacent to each other on the Thiepval Memorial.

The second overseas club referenced in the list is erroneously named as New South Wales. K. Heritage had been a member of the winning Sydney R.C. Grand crew of 1912 which went on to represent Australia at the Stockholm Olympics. As a Captain in the Australian Infantry, he was awarded the M.C. He fell on the 26th day of the Somme Campaign and is buried at Pozieres British Cemetery at Ovillers La Boisselle.

Post Script

Nine of the 273 listed succumbed to injuries between the armistice of 11 November 1918 and the publication of the book in mid 1919. Even while writing the introduction in 1919, the author warned that the list was “subject to revision.”

One of these was W.A.L. Fletcher, DSO, Chairman of the Regatta Committee and Umpire. As an oarsman in the late 1880s and early 1890s, he won four Boat Races with Oxford, two Ladies Plates, and the Thames Cup. He raced three times for the Grand.

Another Henley official who did not survive the war was W.F.C. Holland, a committee member and judge. Rowing at bow behind Fletcher at stroke in the 1890 Oxford crew, his rowing honours included three Boat Race victories in four appearances, three wins in the Grand and one in the Ladies.

Mainzer Ruder-Verein von 1878

In his introduction to the records relating to Henley 1914, Cook wrote, “This Regatta had begun before the murdered Archduke Francis Ferdinand was buried; but the shadow of coming catastrophe was not seen upon the famous racecourse, and we all went home after the meeting without the slightest premonition that it would be some five years before we met again, or that – in the dreadful interval of the coming warfare – so many who were competing in the races of 1914 would be lost to us forever. In one contest that fateful summer there was, as we look back on it, a very singular prognostication of the results to be shown in 1918.” He was referring to the race in the Grand between Jesus College Cambridge and the German club Mainzer Ruder-Verein von 1878.

Mainzer appeared at Henley several times during the early 20th century. In 1914, they were quite possibly en-route to Henley to race in the Grand and Stewards as the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June lit the fuse that would lead to war.

At that time in Germany, all able bodied men between the ages of 17 and 45 were liable for military service: 17 year olds could be called-up to serve in the Landsturm home defence force, similar to the British Army’s Territorial force. On his 20th birthday, if not working in an exempt profession, a man would start two-years of active service. This would be followed by 4-5 years in the reserves with an obligation to attend two-weeks training each year – considered to be something of a holiday from home and work during peace time. After the reserves, men were attached to the Landwehr for a further 11 years. Most Mainzer members were attached to the “Grand Duchess” (3rd Großherzoglich Hessian) No. 117 Regiment, which was garrisoned in Mainz. The regiment had a reputation for its sporting prowess.

The 1914 Grand entry included five members of the Mainzer crew that became the very first of the noble tradition of German eights to take gold at international championships when it won the European Championships in Gent in August 1913. Victory for Mainzer over Jesus College Cambridge by ¾ of a length in their first heat meant that for the first time in its 75-year history, and much to the regret of Cook, all four semi-finalists in the Regatta’s blue-riband event were from overseas. In the closely contested semi-final, Union B.C. Boston, USA, who never led by more than half a length, held on to win by a canvas.

Four from the eight also raced in the Stewards, losing to Leander in their first heat having suffered from steering problems off the start and the collapse of their three-man, Oskar Cordes, as the crews approached Phyllis Court.

Of the Grand eight, we know that Werner Furthmann, Josef Fremersdorf, Oskar Cordes, Lorenz Eismayer and cox Johann Baptist Stohschnitter all survived the war. However, injuries prevented Fremersdorf from returning to the water until 1921 while Cordes, who went on to become a leading figure in the German rowing federation, lost a leg. Eismayer’s brother Konrad also perished.

George Oertel (7) and Erich Vetter (6) were members of both the 1913 European Championship and 1914 Grand crews. Oertel served at Verdun, the Somme and Champagne and was wounded five time, three times seriously. He survived the hostilities but died suddenly in March 1920. Vetter was killed in action. Richard Piez, their crew-mate in the 1913 crew, was also killed in March 1917 while serving as a pilot.

In total, Mainzer lost 39 members to the conflict.

(Many thanks to Rolf Stephan, club archivist and Axel Lang curator of an exhibition on the 1913 European Championship crew for their help with information on Mainzer Ruder-Verein 1878.)

Links

In this World Rowing article to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, Martin Cross describes his own journey in a sculling boat down the Somme and how War and the Somme Campaign has touched the rowing communities of many countries.

For eye-witness accounts of the first day of the Somme, listen to this podcast from the Imperial War Museum

Notes

†The Imperial War Museum website includes a register of war memorials. All clubs which have memorials to members lost to war should check that their’s is included.

‡Beaumont was a Jesuit public school in Old Windsor, sometimes known as “the Catholic Eton”. It closed in 1967.