Since I first posted on my research into the life of Queensberry Rules author John Graham Chambers, I have accumulated more than 700,000 words of research, notes and sources on his involvement in multiple sports up to his premature death in March 1883.

However, as I edit all the material down into something more digestible, I’ve run into a couple of significant, and annoying, discontinuities in the arc of the story. Both relate to the early years of Chambers’ working life.

When I can next arrange a visit to the Trinity and University libraries in Cambridge one of my priorities is to confirm precisely when Chambers graduated. It looks like it was at the end of the summer term in 1865 however he continued participate in the sporting life of Trinity College into the Michaelmas term: he raced, and won, the University Fours for Third Trinity Boat Club in November and entered the Third Trinity athletics meeting in December.

However, by the end of December he was actively involved in setting up the Amateur Athletic Club in London. The AAC was conceived to assume “the same position in reference to athletics that the Jockey Club holds towards racing, or the Marylebone Club towards cricketers.” Some sports historians see the creation of the AAC as the metropolitan elite’s response to the founding of the National Olympian Association by upstarts from the provinces led by John Hulley of the recently opened Liverpool Gymnasium and supported by William Penny Brooks of the Wenlock Olympian Society.

My original post reproduces the article in Land and Water that welcomed the creation of the AAC. I had assumed that the article was written by Chambers. He did certainly go on to write for the weekly which was established as a rival to the Field. He became its editor around 1870.

After Chambers’ death, a detailed 3,674 word obituary in Land and Water talks about how in August of 1865 Chambers didn’t enter sculling events in the summer regatta season on the Thames in order to holiday by rowing along the Danube. The obit continued, “interesting details of the trip from his pen” appeared in the Standard. There are indeed three articles in September editions of the Standard that describe towns along the Danube, but like so much of Victorian journalism, they are not bylined.

The author of the obit is almost certainly Arthur Gay Payne who had been a contemporary of Chambers at Cambridge where he had coxed the Peterhouse eight and represented Cambridge in the varsity billiards match. Payne went on to become sports editor of the Standard, and later became Chambers’ deputy editor at Land and Water. He also wrote several best-selling cookery books! The two of them also supported Matthew Webb in his successful cross-channel swim in 1875. Payne ghost-wrote Webb’s account of his swim.

One recently discovered source talks about how Payne “succeeded Chambers” as sports correspondent at the Standard which has prompted me to question when (and how) Chambers started writing for Land and Water. Of course, it is possible that Chambers contributed to both at the same time.

Despite his relatively high profile as a university sportsman – he was a double rowing blue, had been president of CUBC and was involved in establishing the varsity athletics match in 1864 – I have yet to identify any personal contact who might have introduced Chambers to either publication. There is no obvious connection through his father, who owned a large but not very profitable estate – which included the village of Devils Bridge – in Ceredigion, west Wales.

The second conundrum is the mystery of Chambers’ first wife. As part of my research I had searched the returns for each of the four censuses he lived through. He proved difficult to find in the 1871 census. (Coincidentally, census day was Sunday 2nd April, the the day after the 1871 Boat Race for which Chambers had been one of Cambridge’s finishing coaches.)

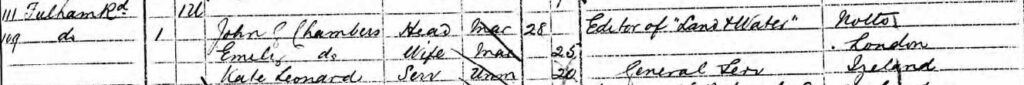

I did eventually track him down – on the Fulham Road in Chelsea. The enumerator incorrectly recorded Chambers’ place of birth as “Notts” rather than any of the possible correct options such as “Llanelly”, “Carmarthenshire” or even “Wales”. But as his profession is listed explicitly as “Editor of ‘Land and Water'”, there is little doubt that this is Chambers’ census entry.

The existence of wife Emily was a real surprise. I was aware that Chambers had married on 24 March 1881 at the late age of 38. However he was described as “Bachelor” on that marriage certificate. His “second” wife, Mary, was the sister of Rigby Melville Wason, another Cambridge contemporary, who went on to become a lawyer. Rigby handled his sister’s divorce from William Henry Urquhart on the grounds adultery and desertion. In what must have contributed to some awkward family gatherings, Rigby Wason was married to Urquhart’s sister!

Having found an earlier wife, I have so far failed to find a corresponding wedding at any time between graduation and census day. Equally, I haven’t found any evidence of a divorce or Emily’s death between the 1871 census and Chambers’ second marriage in 1881. So far, I have found no reason or occasion when John could conceivably have married – or divorced – his nominally London-born wife abroad. It’s a conundrum!

Any suggestions for sources that might shed further light on the start of Chambers’ journalistic career or on the mystery of his first wife would be much appreciated.

(Chambers’ eldest sister was an Emily who had actually been born in London. Sister Emily may have been born in London to minimise gossip among polite society in the then family home of Llanelli: she was born inconveniently soon after her parents’ wedding. However Emily is recorded in her own right in the 1871 census as the 34 year old widow of a baronet, Sir Godfrey John Thomas, living in Brighton. Ironically, the census also records her place of birth incorrectly – as “South Wales”.)